Your Q3 2019 market commentary

Even by recent standards, the third quarter of 2019 was

unpredictable and volatile. Brexit continues to dominate the headlines in both

the UK and in Europe, and the election of a new prime minister appears to have

increased the chances of a disorderly exit from the European Union.

In your Q3 2019 market commentary, we review all the main

economic and political stories of the latest three months, and the latest

economic data.

UK

The third quarter of 2019 began as the previous quarter

had ended: with political upheaval. Boris Johnson won the Conservative

leadership contest and became the UK’s new prime minister in July, promising to

leave the EU on 31 October.

Indeed, he claimed he would rather ‘die in a ditch’ than

ask for another extension; something he may have to do if the courts uphold the

recently passed Benn Act.

Seven Commons defeats and a ruling from the Supreme Court

that his prorogation of parliament was unlawful means it has been an

inauspicious start for the new PM. And, a raft of economic data continues to

show that the UK may be heading towards a recession – even before we have

departed from the European Union.

The

UK economy contracted in the three months to July, marking the first quarterly

decline since 2012. Two consecutive quarters of falling output are the

technical definition of a recession, and analysts are holding their breath for

the next set of official growth figures.

Duncan

Brock, Group Director at the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply,

said: “Deferred client orders and reduced consumer spending as a result of

Brexit uncertainty and a slowing global economy meant hard-pressed businesses

started to lose their battle against the hardest conditions for about a

decade.”

In September, continuing uncertainty also saw the pound touch its lowest level against the dollar

since October 2016. Excluding October 2016’s ‘flash crash’ (when the

pound briefly fell sharply to $1.15 against the dollar before rapidly

rebounding) sterling has not traded regularly below $1.20 since 1985. This is

compared to the rate of around $1.50 before the EU referendum in June 2016.

During August the pound also dropped to

a decade-low against the euro of €1.07.

There was also a negative sentiment among many UK businesses:

- RBS warned that its profits would be hit by

deteriorating economic conditions - HSBC announced 5,000 jobs would be lost as

part of its restructuring efforts - Belfast shipbuilder Harland and Wolff entered

administration

The problems on Britain’s high streets also continued

this summer. Tesco announced that it was cutting 4,500 jobs from its Tesco

Metro stores while Argos owner Sainsbury’s said that it was also planning to

close 50 stores.

The most famous name to collapse this summer was package

holiday firm, Thomas Cook. The travel agent failed to secure capital to see it

through the winter, resulting in the loss of 9,000 jobs and the biggest

peacetime repatriation in British history.

In more positive news, UK inflation fell to its lowest level since late 2016 as the end of

summer sales kept clothing prices down, while economists suggested that some

companies were waiting for the outcome of Brexit before putting prices up.

The consumer price index (CPI) fell to

1.7% in August from 2.1% in July, easing some of the pressure on consumers.

However, economists warned that weakness in the pound since Boris Johnson

became prime minister combined with a no-deal Brexit could push up inflation

again in future.

Europe

Eurozone economic growth is forecast

to slow to 1.1% this year from 1.9% in 2018, which would be its worst

performance in six years.

“German industry is in recession, and this is now also

impacting the service providers catering to those companies,” said Claus

Michelsen, head of forecasting and economic policy at the German Institute for

Economic Research (DIW Berlin).

Italy also saw a flatline in growth, partly due to

continued political uncertainty. Prime minister Giuseppe Conte resigned in

August following Matteo Salvini’s decision to

withdraw from the country’s ruling ‘yellow-green’ coalition, although,

in an unprecedented move, subsequently returned to power at the head of a new

coalition.

With growth slowing in the Eurozone, ECB president

Mario Draghi unveiled a package of measures to ease monetary policy in the

euro area. These included:

- A cut in bank deposit interest rates to -0.5% to encourage lending

- A restart of the ECB’s quantitative easing programme in November, with €20bn of bond purchases each month.

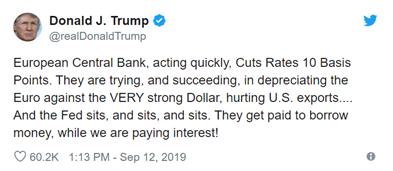

The move met with an immediate response from US President Donald Trump, who controversially claimed the ECB was deliberately weakening the euro to help companies sell goods overseas:

This

prompted a swift rebuttal from Draghi, who insisted that he was simply

following his mandate. He said: “We have a mandate. We pursue price stability

and we don’t target exchange rates. Period.”

US

The economic expansion in the US entered its 11th

year in July, making it the longest expansion

since 1900.

However, as the effects of fiscal

stimulus from the 2018 tax cuts begins to fade, growth has slowed. The

manufacturing sector slipped into a recession during the first half of the

year, and capital investment is also weakening. Recent data from the ADP

Research Institute also showed that hiring at US companies is cooling, with employers

adding just 135,000 jobs in September.

All this means that analysts expect

growth in GDP to slow to 1.7% next year.

July saw the central bank announce its

first cut to its benchmark overnight lending rate in two years – and then

followed this up with another cut two months later. The rate now stands at a target range of 1.75% to 2%,

with the committee citing ‘the implications of global developments for the

economic outlook as well as muted inflation pressures’ as the primary rationale

for the cuts.

Stock markets rewarded the Federal

Reserve with a rally that took the Dow Jones Industrial Average from a

two-month low of 25,479 on 14 August back up to a near-record 27,219 on 13

September.

Rest of the World

In a new report, the United Nations has warned that weaker growth

in both advanced and developing countries means the possibility of a global

recession in 2020 is a ‘clear and present danger’.

The

UN’s trade and development body, UNCTAD, said 2019 will endure the weakest

expansion in a decade and there was a risk of the slowdown turning into

outright contraction next year.

China’s economy continued to falter in the

third quarter after GDP growth slowed to a near three-decade low in Q2

2019.

The ongoing trade war between China and the

US once again escalated again in late August following the US decision to

increase tariffs by 5% on all Chinese goods from 1 October. Although the two

countries agreed to resume trade talks in early October, the likelihood of a

truce anytime soon appears low.

Around the world, low inflation is allowing

central banks to ease their monetary policies to tackle faltering economic

growth. The Fed and ECB both loosened the reins in recent weeks, while Japan

could follow suit before year-end. Among developing economies, China cut the

reserve requirement ratio in August, while Brazil, India and Russia all cut

their interest rates.

Get in touch

Have any queries about your Q3 2019 market commentary?

Please get in touch. Email info@depledgeswm.com or call (0161) 8080200.