8th February 2021

It’s hard to believe that the first confirmed case of human-to-human transmission of coronavirus was just thirteen months ago. Since then, nations across the globe have fought to tackle the spread of the virus, with devastating health and economic results.

With shops and businesses once again closed, the UK is almost certainly heading towards a double-dip recession. And, with the FTSE 100 falling by around 14% in 2020, there looks to be little end in sight for these economic woes.

However, in time, things will start to recover. And history tells us that the long-term economic effects of a major global event, such as the pandemic, may not be as serious as you might imagine.

World War I, Spanish flu, and global cooperation

The 1910s were dark years for the world. As nations were still calculating their losses from the First World War, the Spanish influenza outbreak spread worldwide during 1918 and 1919.

Estimates suggest that about 500 million people, or one-third of the world’s population, became infected with this virus, and that at least 50 million worldwide died after contracting it.

While these two events had a devastating impact, there were some positive outcomes, particularly in terms of wider international cooperation.

The US President, Woodrow Wilson, was one of the architects of the initiative to propose a new world order. Wilson’s famous “fourteen points” guaranteed, among others, the freedom of the seas, and the removal of trade barriers, and he also suggested the idea of an international association to guarantee peace. This became the League of Nations (LON) and, subsequently, the United Nations that we know today.

While the primary role of the LON was to prevent wars – and, by this measure, it failed in its own aims – the prevention and monitoring of infectious diseases was also one of the core missions included in its founding treaty.

For example, the LON established a system of global healthcare cooperation which later helped to defeat typhus in 1922 through the imposition of quarantines and mass examinations.

The LON also worked toward becoming a platform for the global sharing of medical knowledge to help the fight against infectious diseases in an unprecedented manner.

As we tackle the pandemic, the same ideas apply. The core idea that health in a co-dependent world should be safeguarded with international cooperation should be reinforced, which was evidenced by Joe Biden immediately halting the US withdrawal from the World Health Organisation.

In recent months, countries have essentially fought the virus on their own. With greater global cooperation, it ought to be easier to tackle similar health crises in the future. This, of course, would bring significant economic benefits if nations did not have to lockdown citizens or close businesses.

World War II, rationing and health care

One concern many economists have is that consumer habits could permanently change because of the pandemic.

Might we be less inclined to eat (or drink) out once we can? Could we be more reluctant to engage in social activities? Will we stop buying certain items that have become less widely available during lockdown?

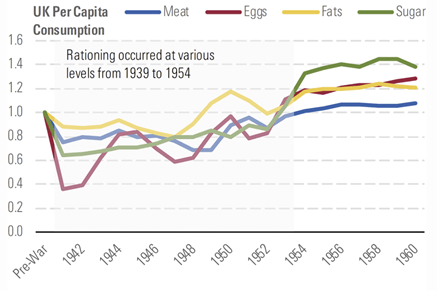

Here, it can be informative to look back at World War II. Of course, during this time, Brits were deprived of a wide range of goods for several years thanks to rationing. It took until 1950 for petrol rationing to end, while confectionary and sugar rationing didn’t end until 1953.

As consumers were deprived of goods for a decade or more, did their habits change? Did consumption of rationed goods fall after the war, even after people regained access to them?

World War II and rationing provides a clear example of people being deprived of goods for several years for reasons outside their control. Did consumers’ habits change, thereby depressing long-run consumption of rationed goods even after people regained access to goods after the war?

Source: Morningstar

This chart shows how the consumption of rationed goods compared during and after the war. It clearly shows that being deprived of goods had little long-term impact on UK food demand, and that demand for rationed goods generally mounted a full recovery.

It suggests that, just because we haven’t been able to stay in a hotel, eat in a restaurant, or drink in a pub for several months, there won’t be a long-term decline in these sectors.

The other major outcome of World War II – at least in domestic terms – was the establishment of the modern welfare state. Post-war, governments around the world invested in people by broadening access to health care.

In advanced economies, the economic benefit of better health care comes from the possibility of creating a longer, healthier middle age. Beyond the clear benefits to individuals, a healthier workforce means people can work longer and more productively.

Could the same happen in 2021 and beyond? Interventions such as weight management, road safety, lower back pain management, and the use of statins could be the investment the economy needs.

In addition, the pandemic has highlighted some of the systemic inequalities in our society. Positive action to tackle food poverty, youth unemployment and other issues could propel the economy forward in years to come. With nations experimenting with new ideas, and ones such as providing all citizens with a basic income gaining traction, the pandemic could be the catalyst for fundamental changes to health and welfare.

The Great Depression and other market crashes

One of the immediate consequences of the coronavirus pandemic was a fall in global stock markets. While many markets rebounded in the second half of the year, by the end of 2020, the FTSE 100 sat 14.3% below the start of the year.

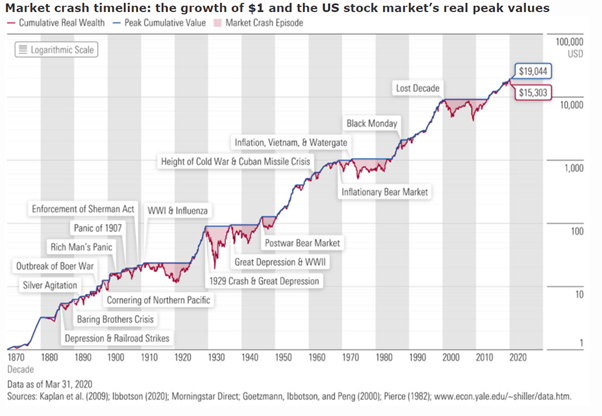

What can history tell us about the performance of stock markets following sharp declines?

According to data from Morningstar, the 1929 crash and Great Depression was the largest fall in US stock market history. The stock market fell by 79% in the aftermath of the crash but had recovered to its pre-crash level by November 1936.

Markets hit a trough in the US in February 2009 during the global financial crisis. This time, recovery took around four years, regaining its peak in May 2013.

The chart below uses real monthly US stock market returns going back to January 1886 and annual returns over the period 1871–85, showing market performance in the US over a period of nearly 150 years.

The chart shows that over this period, $1 (in 1870 US dollars) invested in a hypothetical US stock market index in 1871 would have grown to $15,303 by the end of March 2020.

Of course, it wasn’t a smooth ride to get there. There were many drops along the way, some of which were severe.

Source: Morningstar

The lesson here is that, even in the deepest recessions and severe market falls, markets typically recover. It could take time, but history tells us that the FTSE and other markets will recover – many already have to some extent! – and that the long-term effects of a major event are perhaps not as significant as you might imagine.

Get in touch

If you’d like a professional opinion on investing in uncertain times, please get in touch. Email info@depledgeswm.com or call (0161) 8080200.

Please note

Your capital is at risk. The value of your investment (and any income from them) can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investments should be considered over the longer term and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances.

Comments on 3 historical reasons the long-term economic effects of Covid-19 may not be as bad as you think

There are 0 comments on 3 historical reasons the long-term economic effects of Covid-19 may not be as bad as you think